Chickasaw

|

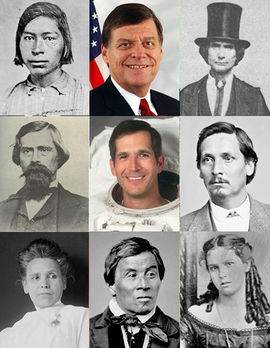

| Top row: Young Chickasaw man, Tom Cole, Winchester Colbert Middle row: Holmes Colbert, John Herrington, J. D. James Bottom row: Mary Hightower (Shunahoyah), Ashkehenaniew, Annie Guy |

| Total population |

|---|

| 38,000[1] |

| Regions with significant populations |

| United States (Oklahoma, Mississippi, Louisiana) |

| Languages |

|

English, Chickasaw |

| Religion |

|

Traditional tribal religion, Christianity (Protestantism) |

| Related ethnic groups |

|

Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek), and Seminole |

The Chickasaw are Native American people originally from the Southeastern United States (Mississippi, Alabama, Tennessee). They are of the Muskogean linguistic group and are federally enrolled as the Chickasaw Nation.

Sometime prior to the first European contact, the Chickasaw migrated and moved east of the Mississippi River, where they settled mostly in present-day northeast Mississippi. The Chickasaw were one of the Five Civilized Tribes, who were forced to sell their country in 1832 and move to Indian Territory (Oklahoma) during the era of Indian Removal. Most Chickasaw now live in Oklahoma. All historical records indicate the Chickasaw lived in northeast Mississippi from the first European contact until the Indian Removal in 1832.

The Chickasaw Nation in Oklahoma is the 13th largest federally recognized tribe in the United States. They are related to the Choctaw and share a common history with them. The Chickasaw are divided in two groups: the Impsaktea and the Intcutwalipa.

Contents |

Etymology

The name Chickasaw, as noted by anthropologist John Swanton, belonged to a Chickasaw leader.[2] Chickasaw is the English spelling of Chikashsha (IPA: [tʃikaʃːa]), meaning "rebel" or "comes from Chicsa".

History

The origin of the Chickasaws is uncertain. Noted 19th-century historian Horatio Cushman thought the Chickasaw, along with the Choctaw, may have had origins in present-day Mexico and migrated north.[3] When Europeans first encountered them, the Chickasaw were living in villages in what is now Mississippi, with a smaller number in the area of Savannah Town, South Carolina. The Chickasaw may have been immigrants to the area and may not have been descendants of the prehistoric Mississippian culture.[3] Their oral history supports this, indicating they moved along with the Choctaw from west of the Mississippi River into present-day Mississippi in prehistoric times.

| “ | "These people (the choctaw) are the only nation from whom I could learn any idea of a traditional account of a first origin; and that is their coming out of a hole in the ground, which they shew between their nation and the Chickasaws; they tell us also that their neighbours were surprised at seeing a people rise at once out of the earth." | ” |

|

—Bernard Romans- Natural History of East and West Florida |

||

The first European contact with the Chickasaw was in 1540, when Spanish explorer Hernando De Soto encountered them and stayed in one of their towns, most likely near present-day Tupelo, Mississippi. After various disagreements, the Chickasaw attacked the De Soto expedition in a nighttime raid, nearly destroying the expedition. The Spanish moved on quickly.[4]

The Chickasaw began to trade with the British after the colony of Carolina was founded in 1670. With British-supplied guns, the Chickasaw raided their enemies the Choctaw, capturing some members and selling them into slavery. When the Choctaw acquired guns from the French, power between the tribes became more equalized and the slave raids stopped.

The Chickasaw were often at war with the French and the Choctaw in the eighteenth century, such as in the Battle of Ackia on May 26, 1736. Skirmishes continued until France ceded its claims to the region after being defeated by the British in the Seven Years' War.

In 1793-94 Chickasaw fought as allies of the new United States under General Anthony Wayne against the Indians of the old Northwest Territory. They were defeated in the Battle of Fallen Timbers, August 20, 1794.

| “ | "Neither the Choctaws nor Chicksaws ever engaged in war against the American people, but always stood as their faithful allies." | ” |

|

—Horatio Cushman, History of the Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Natchez Indians, 1899 |

||

United States relations

George Washington (first U.S. President) and Henry Knox (first U.S. Secretary of War) proposed the cultural transformation of Native Americans.[5] Washington believed that Native Americans were equals, but that their society was inferior. He formulated a policy to encourage the "civilizing" process, and Thomas Jefferson continued it.[6] Noted historian Robert Remini wrote, "They presumed that once the Indians adopted the practice of private property, built homes, farmed, educated their children, and embraced Christianity, these Native Americans would win acceptance from white Americans."[7] Washington's six-point plan included impartial justice toward Indians; regulated buying of Indian lands; promotion of commerce; promotion of experiments to civilize or improve Indian society; presidential authority to give presents; and punishing those who violated Indian rights.[8] The government appointed agents, like Benjamin Hawkins, to live among the Indians and to teach them, through example and instruction, how to live like whites.[5] The Chickasaws accepted Washington's policy as they established schools, adopted yeoman farming practices, converted to Christianity, and built homes like their colonial neighbors.

Hopewell (1786)

The Chickasaw signed the Treaty of Hopewell in 1786. Article 11 of that treaty states: "The hatchet shall be forever buried, and the peace given by the United States of America, and friendship re-established between the said States on the one part, and the Chickasaw nation on the other part, shall be universal, and the contracting parties shall use their utmost endeavors to maintain the peace given as aforesaid, and friendship re-established." Benjamin Hawkins attended this signing.

The Colbert Legacy (19th century)

In the 1700s, a Scottish trader by the name of James Logan Colbert settled in Chickasaw country and stayed there for the next 40 years. His first wife was Minta Hoya, married in 1760, a Chickasaw woman with whom he had seven sons: William, Jonathan, George, Levi, Samuel, Joseph, and Pittman (or James). For nearly a century, the Colbert descendants provided critical leadership during the tribe's greatest challenges. William Colbert once visited U.S. President George Washington. He also served with General Andrew Jackson during the Creek Wars of 1813-14.

Third-generation Colberts, such as Holmes and Winchester, continued the family civic service and political prominence. They helped create the governmental foundation for the Chickasaw Nation in Indian Country (now known as Oklahoma). Holmes Colbert worked on writing the nation's constitution.

Removal era (1837)

Unlike other tribes who exchanged land grants, the Chickasaw were to receive financial compensation of $3 million U.S. dollars from the United States for their lands east of the Mississippi River.[9] In 1836 the Chickasaws had reached an agreement that purchased land from the previously removed Choctaws after a bitter five-year debate. They paid the Choctaws $530,000 for the westernmost part of Choctaw land. The first group of Chickasaws moved in 1837. The $3 million dollars that the U.S. owed the Chickasaw went unpaid for nearly 30 years.

Because the Chickasaws sided with the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War, they had to forfeit their claim to the unpaid amount.[9] The Chickasaws gathered at Memphis, Tennessee on July 4, 1837 with all of their assets—belongings, livestock, and enslaved African Americans. Three thousand and one Chickasaw crossed the Mississippi River, following routes established by Choctaws and Creeks.[9] During the journey, often called the Trail of Tears, more than five hundred Chickasaw died of dysentery and smallpox. Once in Indian Territory, the Chickasaws merged with the Choctaw nation. After several decades of mistrust, they regained nationhood and established a Chickasaw Nation. The majority of the tribe was deported to Indian Territory (now headquartered in Ada, Oklahoma) in the 1830s.

Remnants of the South Carolina Chickasaws, known as the Chaloklowa Chickasaws, have reorganized their tribal government. In 2005 they gained official recognition from the state of South Carolina as a Native American tribe. They have their tribal headquarters at Indiantown, South Carolina.

American Civil War (1861)

The Chickasaw Nation was the first of the Five Civilized Tribes to become allies of the Confederate States of America.[10] They passed a resolution signed by Governor Cyrus Harris on May 25, 1861. Earlier that year the United States abandoned Fort Washita, leaving the Chickasaw Nation defenseless against the Plains tribes. This was their main reason to affiliate with the Confederates.[10]

| “ | But, [Colonel Emory], as soon as the Confederate troops had entered our country, at once abandoned us and the fort; ... By this act the United States abandoned the Choctaws and Chickasaws. | ” |

|

—- Julius Folsom, September 5, 1891, letter to H. B. Cushman |

||

At the beginning of the American Civil War, Albert Pike was appointed as Confederate envoy to Native Americans. In this capacity he negotiated several treaties, including the Treaty with Choctaws and Chickasaws in July 1861. The treaty covered sixty-four terms, covering many subjects like Choctaw and Chickasaw nation sovereignty, Confederate States of America citizenship possibilities, and a entitled delegate in the House of Representatives of the Confederate States of America.[11]

| “ | This was the first time in history the Chickasaws have ever made war against an English speaking people. | ” |

|

—- Governor Cyrus Harris, As Chickasaw troops marched against the Union, 1860s.[10] |

||

Government

The Chickasaws were first combined with the Choctaw Nation and their area in the western area of the nation was called the Chickasaw District. Although originally the western boundary of the Choctaw Nation extended to the 100th meridian, virtually no Chickasaws lived west of the Cross Timbers due to continual raiding by the Indians on the Southern Plains. The United States eventually leased the area between the 100th and 98th meridians for the use of the Plains tribes. The area was referred to as the "Leased District".

Most government services are administrated from Ada.

Treaties

| Treaty | Year | Signed with | Where | Purpose | Ceded Land |

| Treaty with the Chickasaw[12] | 1786 | United States | Hopwell, SC | Peace and Protection provided by the U.S. and Define boundaries | N/A |

| Treaty with the Chickasaw[13] | 1801 | United States | Chickasaw Nation | Right to make wagon road through the Chickasaw Nation, Acknowledge the protection provided by the U.S. | (Not Available yet) |

| Treaty with the Chickasaw[14] | 1805 | United States | Chickasaw Nation | Eliminate debt to U.S. merchants and traders | (Not Available yet) |

| Treaty of with the Chickasaw[15] | 1816 | United States | Chickasaw Nation | Cede land, provide allowances, and tracts reserved to Chickasaw Nation | (Not Available yet) |

| Treaty of with the Chickasaw[16] | 1818 | United States | Chickasaw Nation | Cede land, payments for land cession, and Define boundaries | (Not Available yet) |

| Treaty of Franklin[17] | 1830 | United States | Chickasaw Nation | See Hiram Masonic Lodge No. 7 | [17] |

| Treaty of Pontotoc[18] | 1832 | United States | Chickasaw Nation | Removal and Monetary gain from the sale of land | 6,422,400 acres.[9] |

Post-Civil War

Because of their siding with the Confederacy, after the Civil War, the US government made a peace treaty with the Chickasaw in 1866. It included the provision that they emancipate enslaved blacks and provide them with full citizenship in the nation.

These people became known as Chickasaw Freedmen. Many and their descendants continued to live in Oklahoma.

Today the Choctaw-Chickasaw Freedmen Association of Oklahoma represents their interests. They have expressed support for the Cherokee Freedmen, who are struggling to regain citizenship in their nation after the Cherokee made newly limiting rules on membership.

The Chickasaw Nation never adopted their freedmen into the Tribe as citizens. The only way blacks could become citizens at that time was to be born of a Chickasaw parent or to petition for citizenship and go through the same process as any other race to gain citizenship, if they were not a known blood Chickasaw. Because the Chickasaw Nation had working relations with the Confederacy and did not adopt their freedmen after the Civil War, they were penalized by the U.S. Government who took over half of their lands, with no compensation, which had been negotiated as Chickasaw property in previous treaties for their use due to the Removal from Chickasaw Homelands.

Culture

The suffix -mingo (Chickasaw: minko) is used to identify a chieftain. For example, Tishomingo was the name of a famous Chickasaw chief. The town of Tishomingo, Mississippi and Tishomingo County, Mississippi were named after him, as was the town of Tishomingo, Oklahoma. South Carolina's Black Mingo Creek was named after the colonial Chickasaw chief, who controlled the lands around it as a sort of hunting preserve. Sometimes it is spelled minko, but this most often occurs in older literary references.

Notable Chickasaws

- Bill Anoatubby, Governor of the Chickasaw Nation since 1987

- Amanda Cobb, professor of American studies at University of New Mexico, winner of American Book Award (2001)[19]

- Levi Colbert, Chickasaw language translator

- Tom Cole, Republican U.S. Congressman from Oklahoma

- Molly Culver, actress

- Hiawatha Estes, architect

- Bee Ho Gray, actor

- John Herrington, Astronaut; first Native American in space

- Linda Hogan, Writer-in-Residence of the Chickasaw Nation

- Miko Hughes, actor

- Wahoo McDaniel, pro wrestler, Pro Football

- Rodd Redwing, actor

- Jerod Impichchaachaaha' Tate, composer and pianist

- Fred Waite, cowboy and Chickasaw Nation statesman

- Jack Brisco and Gerry Brisco, pro-wrestling tag team

- Travis Childers, U.S. Congressman from Mississippi

See also

- African-Native Americans

- Chickasaw Nation

- Chickasaw language

- List of sites and peoples visited by the Hernando de Soto Expedition

- Chickasaw Wars

References

- ↑ No Job Name

- ↑ Swanton, John. Source Material for the Social and Ceremonial Life of the Choctaw Indians. The University of Alabama Press. p. 29. ISBN 0817311092.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Cushman, Horatio. "Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Natchez". History of the Choctaw, Chickasaw and Natchez Indians. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 18–19. ISBN 0806131276.

- ↑ Hudson, Charles M. (1997). Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun. University of Georgia Press.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Perdue, Theda. "Chapter 2 "Both White and Red"". Mixed Blood Indians: Racial Construction in the Early South. The University of Georgia Press. p. 51. ISBN 082032731X.

- ↑ Remini, Robert. ""The Reform Begins"". Andrew Jackson. History Book Club. p. 201. ISBN 0965063107.

- ↑ Remini, Robert. ""Brothers, Listen ... You Must Submit"". Andrew Jackson. History Book Club. p. 258. ISBN 0965063107.

- ↑ Miller, Eric (1994). "George Washington And Indians". Eric Miller. http://www.dreric.org/library/northwest.shtml. Retrieved 2008-05-02.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Jesse Burt & Bob Ferguson. "The Removal". Indians of the Southeast: Then and Now. Abingdon Press, Nashville and New York. pp. 170–173. ISBN 0687187931.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Meserve, John (December 1937). "Chronicles of Oklahoma, Volume 15, No. 4". Oklahoma State/Kansas State. http://digital.library.okstate.edu/chronicles/v015/v015p373.html. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. "Choctaw". http://digital.library.okstate.edu/encyclopedia/entries/C/CH047.html. Retrieved 2008-08-11.

- ↑ Kappler, Charles (1904). "INDIAN AFFAIRS: LAWS AND TREATIES Vol. II, Treaties". Government Printing Office. http://digital.library.okstate.edu/kappler/Vol2/treaties/chi0014.htm. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

- ↑ Kappler, Charles (1904). "INDIAN AFFAIRS: LAWS AND TREATIES Vol. II, Treaties". Government Printing Office. http://digital.library.okstate.edu/kappler/Vol2/treaties/chi0055.htm. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

- ↑ Kappler, Charles (1904). "INDIAN AFFAIRS: LAWS AND TREATIES Vol. II, Treaties". Government Printing Office. http://digital.library.okstate.edu/kappler/Vol2/treaties/chi0079.htm. Retrieved 2008-05-02.

- ↑ Kappler, Charles (1904). "INDIAN AFFAIRS: LAWS AND TREATIES Vol. II, Treaties". Government Printing Office. http://digital.library.okstate.edu/kappler/Vol2/treaties/chi0135.htm. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

- ↑ Kappler, Charles (1904). "INDIAN AFFAIRS: LAWS AND TREATIES Vol. II, Treaties". Government Printing Office. http://digital.library.okstate.edu/kappler/Vol2/treaties/chi0174.htm. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Ben Levy and Cecil N. McKithan (February 26, 1973). National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Hiram Masonic Lodge No. 7 / Masonic HallPDF (32 KB). National Park Service. and Accompanying one photo, exterior, undatedPDF (32 KB)

- ↑ Kappler, Charles (1904). "INDIAN AFFAIRS: LAWS AND TREATIES Vol. II, Treaties". Government Printing Office. http://digital.library.okstate.edu/kappler/Vol2/treaties/chi0356.htm. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ↑ "UNM Assistant Professor Wins American Book Club Award." University of New Mexico. September 7, 2001. Accessed June 27, 2007

Additional reading

- Calloway, Colin G., The American Revolution in Indian Country. Cambridge University Press, 1995. see google.com

- Daniel F. Littlefield Jr., The Chickasaw Freedmen: A People without a Country, (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1980).

External links

- The Chickasaw Nation of Oklahoma (official site)

- Chickasaw Nation Industires (government contracting arm of the Chickasaw Nation)

- "Chickasaws: The Unconquerable People", a brief history by Greg O’Brien, Ph.D.

- Encyclopedia of North American Indians

- "Chickasaw History" by Lee Sultzman

- John Bennett Herrington is First Native American Astronaut (on chickasaw.net)

- Tishomingo

- Pashofa recipe

- Tanshpashofa recipe

- Some Chickasaw information in discussion of DeSoto Trail

- Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture - Chickasaw

|

|||||